One of the most serious problems in organizations today is our (ab)use of email. There’s no question that email has fundamentally changed the way people work and how people collaborate. However, now email is often thought of as a scourge: leave the office for a week, come back to 500 emails waiting for you, of which probably 50 require action and 10 are very important.

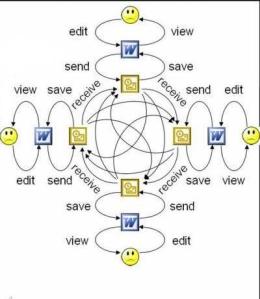

In terms of communication, Email is usually the first resort. Sadly, that means that email is now also most people’s primary means of collaboration. But here’s what email collaboration looks like:

Created by Manny Wilson

Created by Manny WilsonNot exactly the cleanest business process. Not pictured is the person in the middle of the process: the stuckee given the unenviable task of aggregating all of the changes made in the various silos into the “master document”.

Here’s an idea: Try Something Else!

So, as a first step towards improving collaboration: don’t use email. Sounds simple, but of course the difficulty is in the execution. I’ll start with the why. There are several reasons that you should move away from email for collaboration.

- People get enough email: If you can contribute to your colleague receiving less email, I will guarantee you that they will genuinely appreciate it. So, rather than sending out another email to lose in the email, try using another platform!

- Email is not discoverable: To me, this is the most important piece. Email conversations are by definition not discoverable. So if I have a question, I could email five people; unless they forward it on, I am limiting my potential sources of answers. However, if I ask the question in a online, discoverable forum, I can still get the same 5 people to answer the question, but also add everybody else with access to the platform to the potential sources of information. As an added bonus, the knowledge gleaned from the discussion is then captured in a discoverable venue, rather than trapped in an email box.

- Email won’t help you bump into others: One of the great benefits of working in the open is that you can actually bump into people with similar work focuses and similar experiences. Working in a more open environment allows for fortuitous opportunities in order to expand social networks. And given that workforces are becoming more dispersed, this will likely become more important as face-to-face opportunities dwindle.

Executing

Let’s face it, it’s hard to get out of email. It’s been too successful in penetrating the business world. How many times a day do you have a face-to-face or phone conversation that ends with “I’ll type up an email summarizing what we just said”? Well, there are some good ways to start:

- Signal: Rather than sending out questions via email, post the question online and send out the link. It’s still an email, but the discussion and answers will be more discoverable to others

- Do Point-to-Point in the Public: We have a lot more means to talk point-to-point in public nowadays: Wiki User Pages, blogs, Facebook, Twitter etc. Communicating on these is a good first step because they are all more discoverable then email.

- Get out of your comfort zone a bit: Working in the open is a new, weird thing, so it’s not unusual that you would feel strange doing this instead of email. But sometimes you just have to make the leap. Give it a shot. As a colleague tells me, “If you aren’t out of your comfort zone, you aren’t doing your job.”

PS. A note about email notifications. Email works well as a notification for these other tools. Getting an email that says to check a wiki page because it’s changed is inherently different from getting a document in an email, because you can delete the notification and know you won’t be missing information later. If you get a document in an email, you will likely keep that email/document combo because you just don’t know if you’ll need to refer back to it.